Checkpoint Locations & History

from The Western States Trail Guide

Historical Notes by Hal V. Hall

© WESTERN STATES TRAIL FOUNDATION, All Rights Reserved

(Note: the trail varies slightly from year to year, depending on conditions, accessibility, and other factors)

(This file will need to be loaded into a GPS app or unit)

(This file will need to be loaded into Google Earth or Google Maps to view)

See Trail Locations and Historic Notes [coming soon] for more detailed descriptions, images, and video of the trail.

See Crew Guide for more details on crewing for the ride.

Click on the individual points for more information about each location:

Thousands of prospectors flooded into California from 1849 to 1852. Explorations for easier and better routes to the goldfields lead the prospectors to push new trails and wagon roads through the Sierra Nevada. After the “placers” (pure gold nuggets) along the rivers and streams were panned out, the miners moved up the canyons and began drift and hydraulic mining.

Settlements of varied sizes developed in the major mining areas. These communities of tents were built overnight. If the mines in the area were rich, a more permanent settlement with wood buildings was built. But if the mines were poor, the miners literally “pulled up stakes” and moved on. Most of the mining towns were located in remote, mountainous terrain along the canyons of the foothills of the Sierra Nevada.

The hundreds of mining communities were connected by a web of trails and wagon roads up and down the steep canyons.

It is these abandoned towns, trails, and wagon roads that the Tevis Cup trail traverses today.

Click on the triangles to open each section:

Robie Park

Driving Directions:

- From I-80, east of Truckee, take HWY 267 (Exit #188) toward Kings Beach/Lake Tahoe.

- Follow HWY 267 for about 8.5 miles to the top of Brockway Summit.

- Turn RIGHT onto Mt. Watson Road. Stay on Mt Watson Rd., which is paved but narrow. Go slow and watch out for opposing traffic.

- At 6 miles you will see a sign pointing left to Watson Lake, but continue straight ahead on Mt. Watson Road for another 1/4 mile.

- Make a very sharp RIGHT onto the gravel road, Forest Service Road 06. (There may not be a sign at the intersection, but on Ride weekend there will be yellow ribbons.)

- Follow Road 06 for 3 miles (easy down hill) to Robie Equestrian Park.

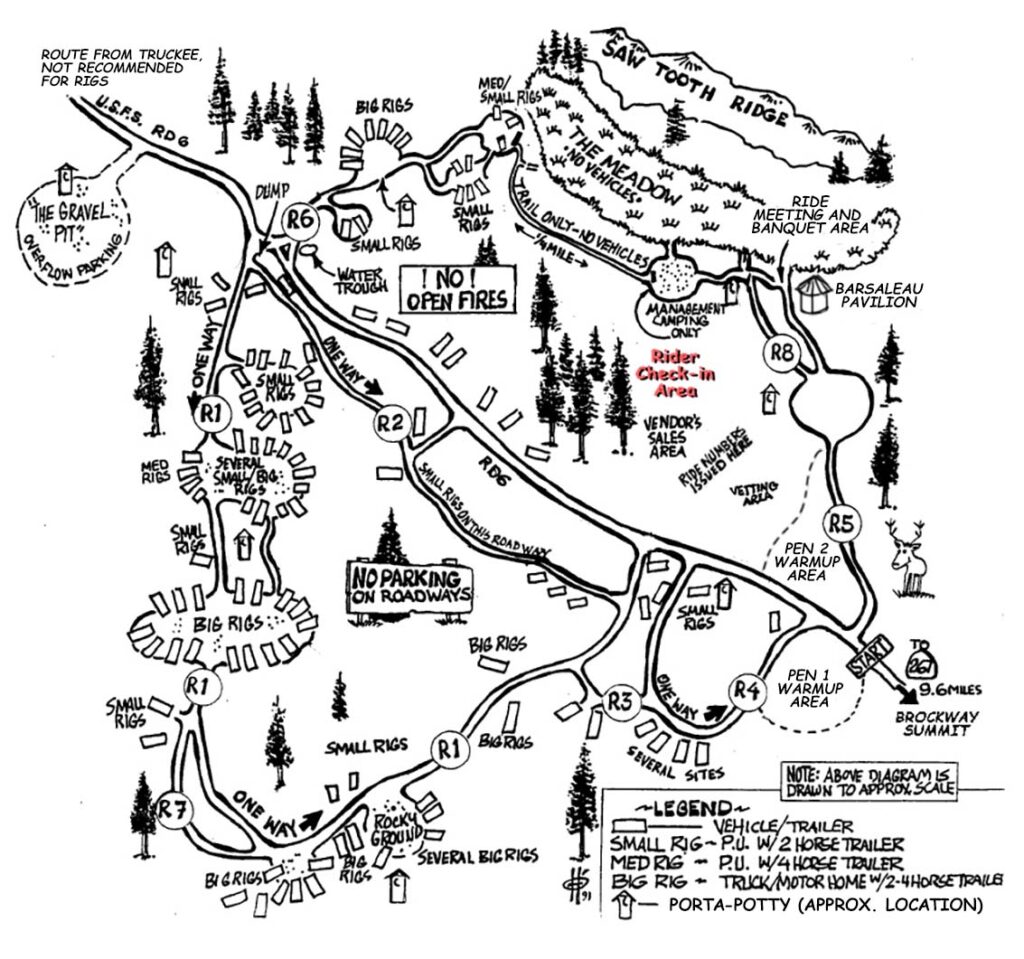

Robie Equestrian Park is made available for use by the Tevis Ride by the Wendell & Inez Robie Foundation. There is a per-horse fee charged for using the park, which is covered as part of the Tevis entry fee.

Visitors to the park during Tevis Weekend are asked to clean up their campsites before leaving by thoroughly spreading horse manure and taking any trash with them.

Camping is available to recreational users throughout the summer months.

On ride day, no vehicles may be started prior to 5:30 am.

Coordinates for the center of the park:

39.23692, -120.17440

Olympic Valley (formerly Squaw Valley)

No crews or spectators (the trail is above the valley floor on the south slope, and then climbs through the ski resort).

There is limited spectator viewing as riders cross under highway 89, approximately 5 miles after the start, however it is not possible to reach this location in time to see the riders if you overnight at Robie Park. (Coordinates for the trail crossing are: 39.19622, -120.19856)

History of Olympic Valley:

Olympic Valley (formerly Squaw Valley) is one of several narrow notched mountain valleys found in the eastern mountain portion of Placer County that was best known in 1862 for summer pasturage for horned cattle, and for dairying purposes. The herbage here was sweet and did not cause distasteful flavor to dairy products, while the cold, pure water insured cleanliness and solidity to the article. Nearly all of these mountain valleys were occupied for this business, and a great deal of butter was made, which, as a rule, had a ready market without leaving the mountains at tourist resorts and the logging and wood-chopping camps and mills.

Two prospectors in June 1863 made their way from Yankee Jim’s, near Foresthill, over the Squaw Valley summit pass into this beautiful mountain meadow. John Keiser and Shannon Knox were vaguely headed in the direction of Carson City when, near the Truckee River just northwest of the mouth of Squaw Creek, they located outcroppings of rich-looking reddish ore. It was rock similar to that in which the Comstock silver lode had been found. A mile up river additional findings were discovered.

The news spread as tales of wealth touched off a rush from the mother lode to the newly discovered area over the short-cut route from the western slopes of the Sierra. Men came scrambling from the Northern California mining towns of Placerville, Georgetown, Last Chance, Kentucky Flat, Michigan Bluff, Hayden Hill, Dutch Flat, Baker Divide, Yankee Jim’s, Mayflower, Paradise, Yuba, Deadwood, Jackass Gulch and all the other camps whose locators and residents had not been as fortunate financially as they were linguistically. These wilderness areas had been transformed into bustling, thriving settlements of miners, merchants, mechanics, gamblers, saloon keepers and bummers, otherwise known as “gentlemen at large.” Nearly six hundred frenzied miners searching for fortune traveled the short cut to arrive at their new destination of hope.

At the site of the first “strike,” the settlement of Knoxville, named for Shannon Knox, boomed. Then Claraville rose up overnight upriver, near the location of the second discovery site. Both locations were pieced together with rough shacks, dirt floor hotels, unorganized main streets, and few having the common necessities. Town lots that had sold a few weeks before for $10 all of sudden were selling for up to $200.

With all of this haste came some bad news. The ore samples had failed to prove out. Some had claimed that the samples were “salted” with ore brought from Virginia City. Yet some of the old timers assert that Knox was “square” and that he firmly believed he had paying ore. So, like an explosion in reverse, a rush in the other direction began. The excitement was gone nearly as fast as it came. In almost six months, the settlements of Knoxville and Claraville which numbered several thousand went from boom to bust as the streets, shacks and mines were deserted. By the beginning of 1864 the camps were all but dead.

Meanwhile, the Prescott brothers had improved the trail from Squaw Valley to Foresthill over the western summit. By April 1864, it was considered “a usable thoroughfare.” Lots in Knoxville and Claraville were purchased at bargain prices by the Prescotts, who hoped to build a permanent settlement with farming and lumbering. And so, for the half century that followed, Squaw Valley settled in as a quiet, high Sierra farming district, a secluded summer range for running cattle.

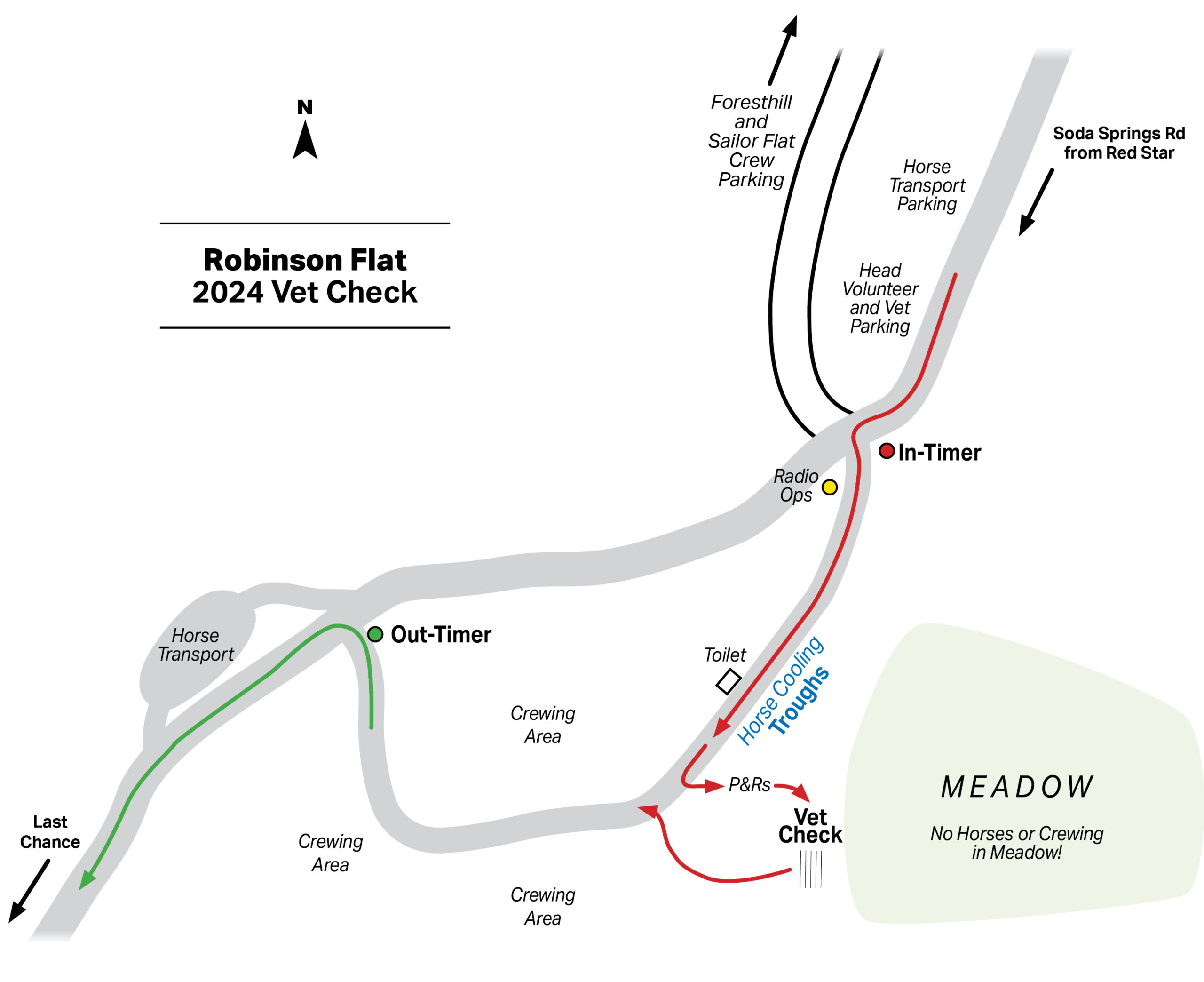

Robinsons Flat – 36 Mile Vet Check

Robinsons Flat is an hour-hold, crew-accessible, full vet check.

Driving Directions:

DO NOT TAKE SODA SPRINGS ROAD SOUTH FROM DONNER SUMMIT.

THIS ROAD IS A VERY ROUGH JEEP ROAD AND AT TIMES IMPASSABLE.

IT IS NOT SUITABLE FOR ROAD VEHICLES.

Allow 2 hours and 45 minutes from Robie Park to Robinsons Flat.

- From Robie Park, follow I-80 approximately 72 miles west to Auburn.

- From I-80 in Auburn, take exit 121 east towards Foresthill on Foresthill Rd.

- Follow the paved Foresthill Rd for 42 miles along the Foresthill Divide, through the town of Foresthill, until you reach Sailor Flat (approximately 1.5 miles below Robinsons Flat).

- Caution – this road is very twisty, and closer to Robinsons Flat has precipitous drop-offs. Please drive carefully.

- Volunteers will direct you where to park.

Upon leaving Foresthill, you will pass the entrance to the Foresthill Mill Site vet check at 18 miles. Many people drop their horse trailers here or in Auburn.

No horse trailers or motorhomes allowed at Robinsons Flat during the ride.

Due to lack of parking, we highly recommend that crews car pool from Foresthill to Robinsons Flat if at all possible.

Note also that at 21 miles from Auburn you pass the turn-off towards Michigan Bluff – this road is used to access both Michigan Bluff and Chicken Hawk should you chose to go there.

If you have a vehicle pass and you arrive prior to the frontrunners getting to the vet check, at Sailor Flat you will be directed to drive your vehicle up to drop off crew / equipment before heading back downhill to park. Please refer to the ride packet for specific instructions and follow instructions from the volunteers.

Vehicles without passes will NOT be allowed past Sailor Flat.

Refer to the Crew Guide for more information.

Coordinates for Robinsons Flat:

39.156414, -120.502837

History of Robinsons Flat

Once a meeting place for local Indian tribes before the white man made his appearance, Robinsons Flat later became a trail crossing and served as a resting place with forage for the livestock of the early-day traveler.

In the grassy meadow of Robinsons Flat, the Drucilla Mason Barner Memorial Foundation placed a granite stone with an inscription dedicating Robinsons Flat as the “Crossroads of the Sierra.”

There is a pump that provides cold potable water in the meadow (no horses please). The Robinsons Flat campground is administered by the Foresthill Ranger District of the Tahoe National Forest.

A mile to the west sitting atop a high cone-like mass of white granite is the Duncan Peak Lookout, which has under observation central California from the high crest of the Sierra in the east, to the Coast Range to the west, and from the far north in the Sacramento Valley to the San Joaquin Valley in the far south. Accessible by road, the lookout is a source of spectacular views of the Sierra and should not be missed.

From the fire lookout, it is possible to see the rooftops of buildings in Foresthill far to the southwest and is a sobering moment for would-be Tevis riders to see the distance they must travel to get to that location.

Last Chance – 50 mile Vet Check

No crews or spectators at this checkpoint.

Coordinates for this location are: 39.11056, -120.62553

Because this vet check is NOT open to crews, the Ride provides water and feed for the horses and refreshments for the riders.

History of Last Chance

The search for golden treasures led a group of prospectors into this remote region in the summer of 1850. Climbing to the top of a ridge, they stopped to prospect at the end of a point of rocks that jutted high above the river. Several rich deposits discovered in the vicinity caused them to linger until all the provisions were gone and starvation threatened.

One of the company possessed a good rifle with one bullet left. Saying to his companions, “This is our last chance to make a grub-stake,” he went into the forest, and returned with a large buck. Thus the miners were able to return to their diggings and a new camp earned its name. This is one of several versions of the origin of the name, “Last Chance.”

Deadwood – 55 mile Vet Check

No crews or spectators at this checkpoint.

Coordinates for this location are: 39.09022, -120.67562

Because this vet check is NOT open to crews, the Ride provides water and feed for the horses and refreshments for the riders.

History of Deadwood

What was once a thriving Sierra Nevada mining town is marked now by the tumbled remains of a well house and a few rotten beams from the old hotel. Even the foundations of the buildings are not as they were. Relic seekers of this and other generations have burrowed under them in their search for souvenirs. Nonetheless, here along the Western States Trail, at the tip of a narrow mountain spur that rises high above the chasms of El Dorado Canyon and the North Fork of the Middle Fork of the American River, is the site of the once glorious town of Deadwood.

The town acquired its name in the same haphazard manner as other mining towns of the era. Gold in paying quantity was first found in Deadwood in 1852 by a group of prospectors who up to that time had not been too successful. They happily remarked to other newcomers that they now assuredly had the ‘deadwood’ toward securing a fortune — in other words, it was a cinch.

The first discoverers of gold in this locality were so positive of its richness and magnitude, their most flattering accounts of the gold strike spread, and a great influx of people resulted. The heartening news that was circulated about the Deadwood discovery caused a bustling camp to spring up, composed of over 500 miners who had toiled over fearful canyon trails to reach this remote spot. It was a wild, austere habitat, to which only the most venturesome came.

Varying estimates are made of the population, but it is known that 800 votes were cast there in the election of 1860, which would indicate an approximate population of 1500 at its peak. Many of the buildings erected were substantial, considering the isolated location of the town. Some hydraulic mining was done, but the principal mines were worked through tunnels by drifting and washing the gravel. As of 1881 there were five claims working that were original discovery locations. Most of the mines were located right in town.

When Anne Ferguson McCauley was still alive she told of her parents, Jessie and Duncan Ferguson, who ran the Half-Way House Hotel in Deadwood: “It was half-way between Michigan Bluff and Last Chance for the miners to rest, eat and drink,” she related. “There was a large outdoor platform where they drove the mules to for unloading their packs. On July 4th the platform was used for dancing as everybody came from miles around, mostly by mule or horseback, as there were only narrow trails at that time. They usually celebrated a whole week.”

In later years the hotel continued in operation as a boarding house, and because of its location, escaped destruction in the forest fire of 1924. However, its complete demise came several years later when the timbers of its remaining structures were salvaged by a prospector for use in building his cabin in the canyon below.

Jessie Ferguson was a colorful character at the center of the miners’ lives in Deadwood for many years. As Anne McCauley recounts, “When the school was closed Jessie taught her own children as well as others. School was kept until the pupils gave out; when they got down to one they just closed the school. She was also the only doctor that many of them knew. She had a large old fashioned doctor’s book, and with the help of it she managed to take care of the community. She delivered nearly all the babies. People would come to her any time, day or night, for aid. Many times in winter she would put on her big rubber boots, a heavy raincoat and, with her trusty doctor’s book, go out in the middle of night in storms to aid the sick. She never received any pay except gratitude for all her kindness. She also preached the funeral services if anybody died.”

As with most of the early gold mining towns, however, Deadwood gradually died. The town’s transient glory in great measure departed by 1855, although mining with moderate returns continued until the last family moved out in 1906. In 1924 a forest fire wiped out the ghostly buildings that remained, save only the old hotel. Even the cemetery at the end of the point was eventually bulldozed under, its silent story lost: Its tombstones were faintly discernible with names like Maxan, Cusick, Jones, Newman, Peters, Cook, Grant, Frier, Harkness, Snyder, Green, Taylor, Williams and Ebbert.

Gone, too, are the Sundays of the solitary prospectors, usually spent in baking bread for the week, grinding a supply of coffee, washing and patching clothes, hunting or fishing. For most miners, Sunday meant a trip to town to buy provisions for the week, get their letters from home, visit with friends, drink, gamble, and enjoy the excitement of the scene. The day no longer exists where, as for the miners of Deadwood, dressing up once meant “washing the face and hands, taking a fresh cud of fine cut (Mrs. Miller’s Brand), or donning a clay pipe well stocked.” Only an old well remains at the town site, if you know where to look.

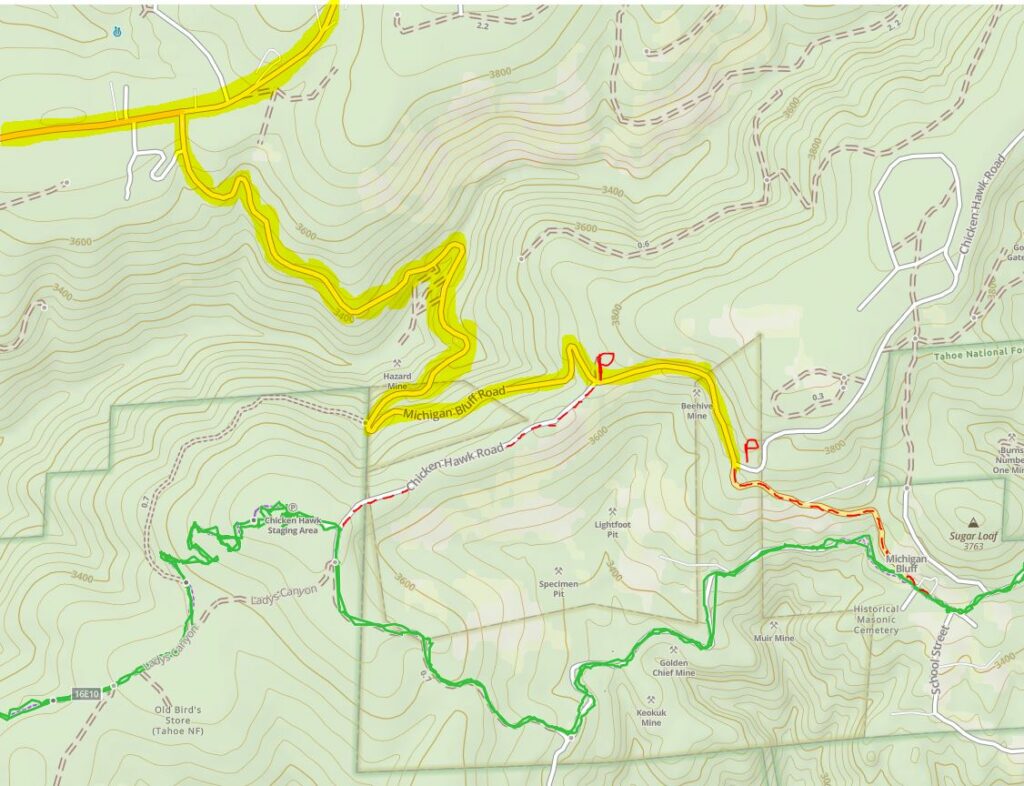

Michigan Bluff – 62.5 miles and Chicken Hawk – 64 mile Vet Check

Crews and spectators allowed at these two locations.

Michigan Bluff is a water stop, while Chicken Hawk is a full gate-n-go vet check – both require hiking on foot to reach them.

Driving Directions:

- From Sailor Flat below Robinsons Flat, backtrack towards Foresthill and travel 21 miles until the left turn to Michigan Bluff, or

- From Foresthill Mill Site, turn right onto Foresthill Road and travel 3 miles until the right turn to Michigan Bluff.

- Continue on Michigan Bluff Road until:

- For Chicken Hawk, after 2 miles, you will get to Chicken Hawk Road on the right. Park off the pavement and hike in 0.6 miles (level) on the dirt road to the vet check.

- For Michigan Bluff, after 2.4 miles, a volunteer will direct you where to park. You will hike in 0.5 miles (250 ft descent) on the paved road into the town of Michigan Bluff.

Note that online map instructions to get to Chicken Hawk Road will often take you to another, unrelated, part of the road further east.

Coordinates for Michigan Bluff are: 39.04138, -120.73602

Coordinates for Chicken Hawk are: 39.04355, -120.75874

Michigan Bluff was the original location of the second hour-hold vet check (now located in Foresthill), however since the start of the ride moved to Robie Park and various other trail changes, as well as development within the town itself, it is now just a welcome water stop as riders climb out of El Dorado Canyon – a chance to get their horses a drink and get cooled off before travelling 1.5 miles to the full vet check at Chicken Hawk and onwards to tackle the final canyon – Volcano Canyon.

Chicken Hawk is a relatively new staging area – developed in part due to the hard work of WSTF president Bill Pieper*. In 2021, WSTF drilled a 350 ft-deep, 100 gpm water well at the site – which helped greatly with some of the logistical problems of supplying water during the Ride – and later that year a double-vault toilet was added.

Horse camping is encouraged (although during the winter months the site is inaccessible). At this point, there is no infrastructure (permanent pump or tank/trough) at the well head—that’s part of Phase 2—but if a group would like to use Chicken Hawk to stage a camp out, arrangements can be made to hook up a generator and water tank for their use.

(* Bill Pieper left us in 2014, but amongst his many, many contributions to WSTF, he served as president for 10 years and was ride manager for six. Click to read more about Bill’s influence on the WST and the Tevis cup)

History of Michigan Bluff

High upon the brow of the Middle Fork and El Dorado Canyons, some two thousand feet above their respective rivers, clinging to its steep slopes is a quiet little ghost town with its great days behind it, Michigan Bluff. At one time its mines shipped out $100,000.00 in gold each month.

Blasting, washing, and sluicing for gold had devastating effect, as the face of the countryside changed. What might have taken centuries to accomplish by natural erosion was produced in a very few years. Soil to a depth of 150 feet was washed from acres of land, using high-pressure water, leaving only bedrock exposed. Slopes stripped of trees and chaparral then became subject to accelerated erosion and landslides.

As they continued to wash the ancient river channel, the miners found their city above on the canyon edge beginning to move. Michigan City began to settle and slip, threatening to precipitate the town into the abyss. In 1859 the city was moved to its present site.

Between 1849 and 1850, mining camps located along the present-day Foresthill Divide were difficult to reach by foot, or by wagon. By 1851, the business communities of Michigan City (later Michigan Bluff), Deadwood, and Last Chance, were doing well, and the population was increasing, as was gold production. Many of the camps such as Deadwood and Last Chance could only be reached by foot, pack trains, or by horseback along a precipitous trail. Millions of dollars in value and several tons in weight of gold were packed out by mule trains over many years along the Michigan Bluff to Last Chance trail.

The Michigan Bluff to Last Chance section of the Western States Trail was built in 1850 and later became a maintained toll-trail, perhaps one of only a few toll-trails in the state. Toll price for people walking the trail was 25 cents.

While stages and mail service operated along the newly established roads, perhaps, of more importance were the freighters who supplied the camps with foodstuffs, clothing, mining tools, medicine, and many other supplies. During the early 1850’s most camps were dependent upon the local freight companies, particularly during the winter months, when access in and out of the camps was more difficult. Supplies were brought in by large pack-trains of mules, rather than by wagons.

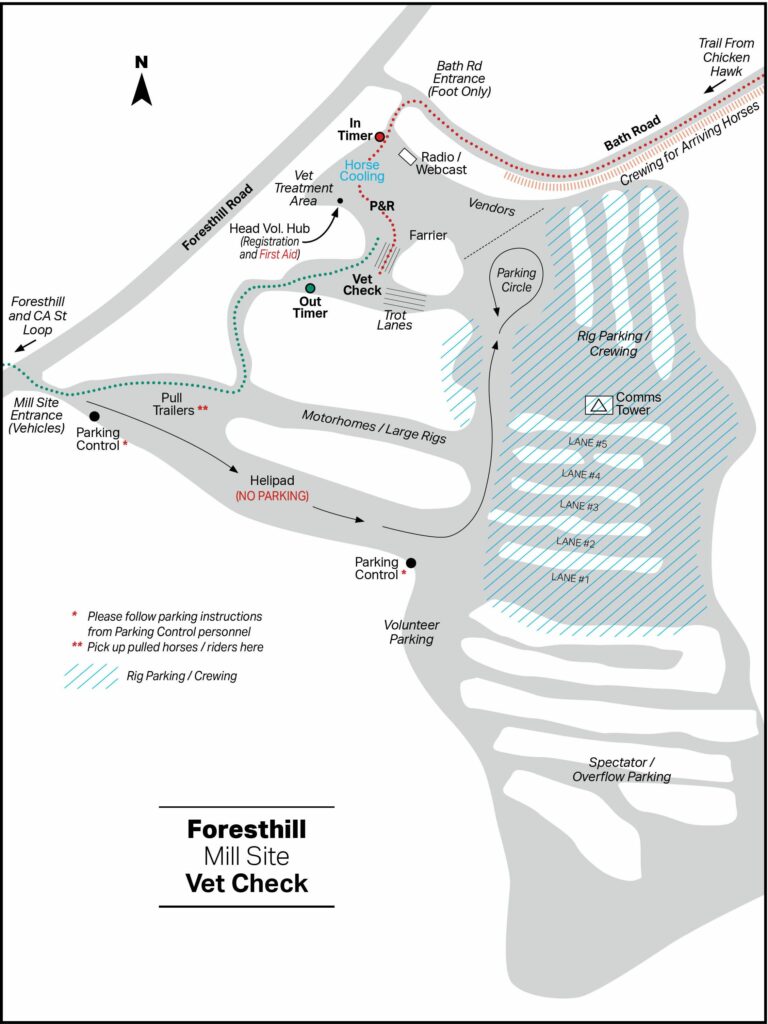

Foresthill – 68 mile Vet Check

Foresthill is an hour-hold, crew-accessible, full vet check.

Foresthill is located northeast of Auburn, about 17 miles from I-80 along the Foresthill Divide Road. Foresthill is the last bit of “civilization” that riders encounter before dropping back down into the canyons for the remainder of the Ride. The main business section is a quarter-mile strip of Gold Rush era buildings, complete with the classic square false fronts on their upper stories. .

The Foresthill Vet check is held at an old sawmill site just east of the business section. Riders enter the site from Bath Road, a narrow paved turnoff from the Divide Road that winds downhill to where the trail from Michigan Bluff climbs out from the Volcano Creek canyon, joining about a half mile below the mill site.

Foresthill is the most accessible of all the vet checks where crews are allowed in to meet their riders. Unlike Robinsons Flat, the Foresthill mill site has acres of level dirt / gravel parking space for trailer rigs. It is strongly suggested that crews leave their rigs at Foresthill and carpool the rest of the way to Robinsons Flat, farther east along the Divide.

Tevis Cup Weekend is a major event for the Foresthill townsfolk. The trail out of the mill site area follows the Divide Road down through the business section. The locals bring chairs out in the afternoon and cheer on the passing riders from their porches and front lawns until well into the evening.

Foresthill is generally the last part of the trail that riders see by daylight. Although some of the front runners make it much farther before nightfall, many riders are happy just to clear Foresthill before dark.

Near the west end of town, the route jogs to the left for one block and continues west on California Street. The pavement ends about 100 yards along, and the route becomes a single-track trail that immediately crosses another paved road, Mosquito Ridge Road. This “California Street Trail” then proceeds into the canyon of the Middle Fork of the American River, the southern flank of the Foresthill Divide.

Francisco’s – 85 mile Vet Check

No crews or spectators at this checkpoint.

Coordinates for this location are: 38.96353, -120.93116

Francisco’s is a natural meadow of about two acres in size that overlooks Oregon Bar, about 100 yards away. Oregon Bar is named for a party of Oregonians who found gold there in the summer of 1848. It was later the site of the Greenwood/Ponderosa bridge which provided a direct road link between the Greenwood area on the south side of the river and Foresthill on the north. The bridge was carried away by a flood in the winter of 1964 and was never rebuilt.

Above the meadow, an old unpaved two-track road winds its way up the hillside to White Oak Flat. The 1997 Tevis Cup Ride made use of the original Tevis Cup trail through the Todds Valley area to White Oak Flat, branching off from a point on the “California Street” trail, known as “Cal-2.” The vet check usually held at Francisco’s was held at White Oak Flat that year. The trail route then proceeded downhill to Francisco’s.

Because Francisco’s Vet check is NOT open to crews, the Ride provides water and feed for the horses and refreshments for the riders. In the event that a horse is pulled, there is a gravel road nearby that ascends through Drivers Flat to the Foresthill Divide Road. Only Ride volunteers are allowed to trailer horses and their riders out of Francisco’s, as the road out is very steep.

Lower Quarry – 94 mile Vet Check

No crews or spectators at this checkpoint.

Coordinates for this location are: 38.91460, -121.02465

The Lower Quarry Vet Check is held in an open area along the railbed of the old Mountain Quarries narrow gauge railroad. The rail bed follows along the river on the lower edge of a limestone quarry that has been in operation since the late 1800’s. Upon departing the vet check, riders continue along the course of the old rail line, crossing Highway 49 and then No Hands Bridge, historically known as the Mountain Quarries Bridge.

This vet check location is referred to as the “Lower Quarry” since in past years, and as recently as 1996, the ride course has taken a somewhat different course. In those cases, the vet check was held in a truck weigh station yard in the “Upper Quarry” area, immediately beside Highway 49, about two miles from the town of Cool. After crossing the road, the trail winds along above the highway, rejoining the lower route just before No Hands Bridge.

In the early 1900s, a local dentist, Dr Hawver, explored a limestone cavern who’s entrance is just above the current vet check. The remains within included saber-toothed tigers, mammoths, dire wolves, and giant ground sloths, as well as four human skeletons determined to be 10,000 years old.

The Quarry Vet check is NOT open to crews. The Ride provides water and feed for the horses and refreshments for the riders. In the event that a horse is pulled, the railroad bed provides trailer access to Highway 49.

No Hands Bridge – 96 miles

Crews and spectators are allowed at this location.

Coordinates for this location are: 38.91256, -121.04173

In the late 1960’s, after a “modern” highway bridge just upstream washed out in a major flood, No Hands served for months as the only direct link between Auburn and Cool. The rails shown were added for safety while a new highway bridge was being built.

No Hands Bridge was closed in the Spring of 1996 due to erosion of the center pier’s footing.

In order for the Ride to get permission to use the bridge during this time, seismic sensors were placed on the structure and monitored throughout the evening.

If the slightest movement was detected, there was a plan in place to reroute riders to cross the river via the highway 49 bridge. If you look carefully, you can still see evidence of the sensors placed across the expansion joints on the bridge.

It was reopened for limited use in late December, 1997, following successful stabilizing repairs. During September and October, 1999, the bridge was closed again briefly for final repairs. No Hands Bridge has been open without restriction to foot traffic and equestrians since late 1998.

After crossing the bridge there is a mild upward grade along the former rail route that parallels the river. The rails and the trestles that once spanned the creek ravines are long gone, having been salvaged for the War effort in the 1940’s. After about two miles the trail leaves the railbed and climbs to cross Robie Point. Within another two miles you will arrive at the Finish Line, the Western States Trail Staging Area near the Gold Country Fairgrounds.

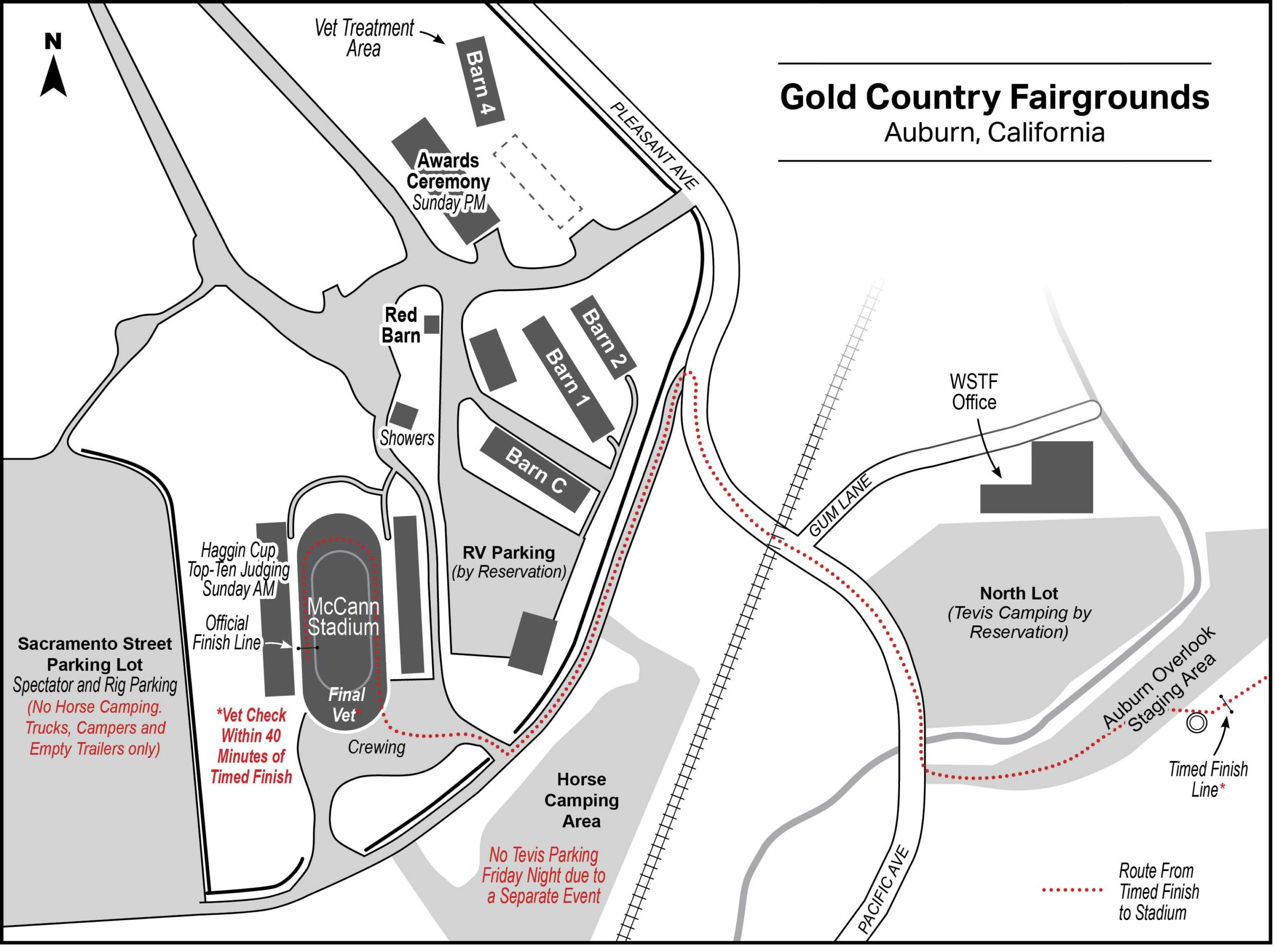

Finish Line and McCann Stadium – 100 miles

The “Timed Finish Line” is located in the “Auburn Overlook” area near the Auburn Fairgrounds. The Overlook was originally developed in the 1970’s to provide parking for visitors to view the Auburn Dam. The dam was then under construction in the canyon below, but work was suspended due to uncertainty about the seismic stability of the site. If it had been built, the Auburn dam, would have submerged most of the final third of the Ride course, including No Hands Bridge, under hundreds of feet of water.

The “Ceremonial Finish Line” is in McCann Stadium at the Gold Country Fairgrounds where rider and horse take the finishers’ victory lap and undergo a final “fit to continue” vet check.

The awards ceremony is held the next afternoon (Sunday) at the Fairgrounds.